The following is the transcript of a talk I gave at the 2013 U of T Worlds AIDS Day Commemoration Event on November 27, 2013. It has been one year since I wrote and delivered this, but only now do I have the gumption (if you will) to share it more widely. I needed to pick a title before I actually wrote the speech, but the essence of it comes through my many interactions with youth involved in the HIV and AIDS response. I recognize that I am only one voice but this is a call for us to all start using our voices and sharing our stories around HIV/AIDS.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Our Collective Youth Voices against HIV and AIDS

Hello Everyone,

Thank you all for being here at U of T’s 2013 World AIDS Day event. We are gathered to show our support for people living with HIV and to commemorate those who have died. I’m extremely grateful to have the opportunity to speak here today. I have been involved in HIV/AIDS research, education and programming and I wanted to acknowledge that some great research is being done in this area and I think Dr. Jha may be speaking more about that soon. However, today, I want to address HIV/AIDS from a youth perspective and make this a conversation that is more personal. I would like to share some of my personal experiences around HIV/AIDS. I’m going to share 3 stories with you.

The first story is about the importance of knowledge.

The setting for this story is right here in Toronto, while I was with the organization Africa’s Children-Africa’s Future (AC-AF). About a year and a half ago, I was co-facilitating HIV and AIDS workshops for high-school students in a priority neighbourhood. The workshop took place over 3 days with a class of 7th grade girls who were around 14 years old. We talked about some of the basic knowledge and science around HIV and AIDS. What is it? How is the virus transmitted? Some of the girls thought that HIV can be transmitted through toilet seats. It can’t be. Many weren’t sure if sharing eating utensils with someone living with HIV is safe. It’s completely fine. This uncertainty creates confusion about the facts, which in turn leads to understandably wary behaviour which is exclusionary.

In these workshops, the girls were allowed to submit questions anonymously into a big box. These questions would then be answered in front of the whole class the following day. With the shield of anonymity, the questions were more honest, more raw and more telling than I could have predicted. “How do I know if I have HIV?” “Where can I get tested for HIV?” These questions from 14 year-olds in Toronto were incredibly enlightening. Take a moment to think about what those questions mean. “How do I know if I have HIV?”

I am Sri Lankan but I grew up in the United Arab Emirates and my family is fairly religious. No one was talking to me about these issues and I have to admit that my knowledge on the subject was severely limited. I had never even heard about HIV/AIDS before I came to live in Canada at the age of 17. That’s not to say it doesn’t exist there. I had a fairly sheltered childhood and the assumption was made by those around me that instilling in me that certain behaviours were wrong and bad would be enough to deter me from high risk behaviours. It was assumed that I just didn’t need to know. In a different place, in a different time, I honestly don’t know if that would have been enough.

So when I think of my 14 year old self in a different situation, I think of the 14 year old girl here in Toronto who asked that question “How do I know if I have HIV?” If that 14 year old had known the facts, maybe she wouldn’t be asking that question anonymously or at all.

Wondering whether something could have been prevented if only you had known the facts, is a horribly overwhelming and destructive feeling. Having the knowledge gives you the ability to make informed decisions. Knowledge about higher risk behaviours. Knowledge about transmission. Knowledge about your HIV status. Once the girls realized that HIV and AIDS is not just something that is far away in a different country that is someone else’s problem, it became more real. HIV/AIDS is right here in Toronto, in Canada and it’s a reality for all of us.

The second story is about consequences.

This story is about a 22 year-old that I met last year prior to the 2012 International AIDS Conference in Washington DC. I had the opportunity to attend the Youth Pre-Conference which brought together 200 young people from around the world – different backgrounds, different languages, different experiences. This was where I learned that globally, youth aged 15 to 24 account for 41% of newly reported HIV cases. That’s a staggering number. 41% of new HIV cases are among young people between the ages of 15 and 24.

This 22 year old was the very first person that I spoke to at that conference. Initial shyness gave way to curiosity … after all, we were both there because we were actively involved in the response to HIV/AIDS. He was from Botswana and working with the lesbian, gay and bisexual community there to promote awareness and education around HIV/AIDS. The double stigma that comes with not being heterosexual and having HIV/AIDS in the cultural context of Botswana is one that I can only imagine. His work within this population was necessary but in his words “was tough”. He was open-minded to learning about my background and my experiences. We became fast friends and kept in touch after the conference with the promise of meeting next year at AIDS 2014.

Sadly, this month, on November 5th, I learned that my friend in Botswana had committed suicide. His death… highlighted for me the importance of mental health in the context of HIV/AIDS. HIV/AIDS is a global, public health concern which also has immense social implications. The need has never been greater for a society that allows you to be who you are and a system that enables you to seek support. He is one of the main reasons I welcomed this opportunity to speak with all of you today. He strongly believed in the work he was doing. Correlation is not causation. But he was working in the field of health and was a strong individual so it is telling that he did not get the support that he needed.

Sadly, this month, on November 5th, I learned that my friend in Botswana had committed suicide. His death… highlighted for me the importance of mental health in the context of HIV/AIDS. HIV/AIDS is a global, public health concern which also has immense social implications. The need has never been greater for a society that allows you to be who you are and a system that enables you to seek support. He is one of the main reasons I welcomed this opportunity to speak with all of you today. He strongly believed in the work he was doing. Correlation is not causation. But he was working in the field of health and was a strong individual so it is telling that he did not get the support that he needed.

Today, even voicing your opinion can have consequences. But I and at least the 200 other youth at that conference strongly believe that shouldn’t be the case. As young people, there are greater consequences to not speaking about these issues. We have much more to lose. We keep hearing about ending AIDS in our lifetime and yet year after year there continues to be new infections.

The third story is about change.

At this youth conference last year, I was asked a personal question. I was asked whether if I was diagnosed with HIV today, if I would share this information with my close family – parents, siblings, partner etc. At the time, I didn’t have to think about it for very long. And to be very honest here, my immediate reaction was “No” – how could I share information like that with my parents. HIV/AIDS is often associated with behaviours that are unacceptable – often from a specific perspective which could be a religious or cultural point of view. People immediately think – sex, drugs? And that’s a scary conversation to have with anyone’s parents.

If you were diagnosed today, would you be able to share this information with those closest to you? Some of you may have had to deal with this situation. Some of you may be fortunate enough to be thinking, yes, I would be able to share this with my father or my sister or my partner. As a young person, I am extremely aware that my culture, religion, gender, sexual orientation and other factors have had roles to play in defining who I am, influencing what behaviours I engage in and building my perceptions of society. Because of these characteristics, I, like everyone in this room, have a unique outlook which needs to be put into context.

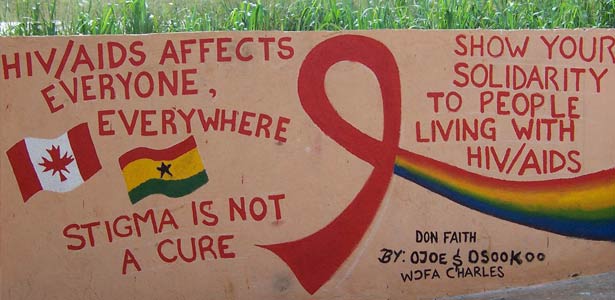

So how do we get there? How do we get to a place where it is okay to talk about these issues. Because once we get to that point of talking about it, that means there’s a better chance of preventing transmission. It means there’s a better chance of someone get tested and someone getting treatment. It means there’s a higher chance that someone can live openly with HIV/AIDS without fear of stigma or discrimination. The stigma associated with HIV/AIDS is still unacceptable and we need to change that.

So I asked myself where do we start, and I realized that I need to be willing to participate in change myself.

Fairly simple concept, def initely easier said than done. So it has taken some time, but now I like to think that I would change my answer to that question.

initely easier said than done. So it has taken some time, but now I like to think that I would change my answer to that question.

Culture, religion and all those factors in mind, this is why I am sharing these stories with you today. When we’re all so different, how do we start to understand one another? We need to start talking to one another. But more importantly we need to start listening to one another. This is a crucial step in making change happen.

In the next few days leading up to World AIDS Day and beyond that, I hope we can, with renewed energy, continue to have these conversations, share our knowledge and keep in mind the consequences. I have shared 3 of my personal stories, and I hope that you will all continue by sharing yours.